Central to the Anglo-American imperial world view, Western political institutions tend to claim ‘our democracy’ as a unique asset – a modern, polite way of claiming that ‘Western civilization’ is superior to others. The standard history says democracy was invented in Athens, mysteriously passed into the Magna Carta in England, to find its most perfect home in the United States of America where The Founding Fathers, in communion with God, transcribed a flawless constitution. Anglo-American universities, think-tanks and opinion-leaders have spread the good word ever since, for it is they who judge the health of democracy in the world. Jeff Rich

America’s Founding Fathers guessed that a native monarch, democratically elected by propertied white men like themselves, could run the country better than an unelected absent monarch. Says Lincoln’s Secretary of State, Henry Seward, “We elect a king for four years and give him absolute power within certain limits which, after all, he can interpret for himself”. Presidential powers have grown since Lincoln’s day to include total control of all media, censorship, kidnapping, torture and assassination of anyone anywhere, and the killing millions of civilians in wars.

With few exceptions, Western governments act like the monarchs they overthrew, accountable to bankers and wealthy elites, consulting their citizens only in times of dire need and never following their expressed wishes, telling the truth, or keeping their promises. Like their royal predecessors, they wasted blood and treasure on foreign wars, oblivious to the needs of their people and the weakness of economies undermined by trillions in war debt, and so estranged from their electorates that just 31% of Americans and 33% of Brits expect them to do the right thing.

Forty years ago, when millions of unemployed Britons complained about her governing style, Margaret Thatcher was unsympathetic: there is no alternatives to monarchical governance, she told them.

But now there is.

“Part with the food”

Confucius' disciple asked him about the essence of good government and the Master replied, “The requisites of government are that there be a sufficiency of food, enough military equipment, and the confidence of the people in their ruler.”

The disciple asked: “If it were necessary to dispense with one of these, which of the three should be done without?” Confucius answered, “The military equipment.”

He asked again, “If it were necessary to dispense with one of the remaining two, which one should be foregone?”

“Part with the food. Death has always been the lot of men; but if the people have no faith in their rulers, then the state cannot exist.” Analects.

Today, six billion people in the developing world are enthralled by China’s narrative, told wordlessly by the dozens of railways, hospitals, stadia and ports, hundreds of power plants and schools it has built around the world. Its staggering economic growth and its victory over poverty speak volumes.

Confucius’ breakthrough

Upper class Chinese have obsessed about governance as far back as records go. When Confucius was born around 500 BC, the Duke of Zhou (1000 BC) was still fondly remembered for his decades of wise, peaceful, prosperous governance, for turning over the enlarged, enriched kingdom to the young heir, and for retiring to compose music and write poetry still that is still read today. Confucius had found the model and the Golden Age he needed to anchor his central argument:

Let people see that you only want their good and the people will be good. The relationship between superiors and inferiors is like that between the wind and the grass. The grass must bend when the wind blows across it. If good men govern a country continually for a hundred years they will transform the violently bad and dispense with capital punishment altogether. Analects.

Confucius observed that, if people genuinely admire their leaders they will cooperate with them. “If you permit only highly effective moral standouts like the Duke to govern, and weed out grifters and power-seekers, he said, you can govern the country easily and inexpensively. He labeled highly effective moral standouts like the Duke junzi1, moral and intellectual princes whose mere presence in government would sustain a dynasty indefinitely and maintain a genuinely meritocratic society.

But no kings were interested in his scheme and, convinced that he had failed, Confucius died.

For the next six centuries his disciples kept his teaching alive among the intelligentsia and officials until young emperor Taizong, already a successful general, realizing that running a country was more difficult than winning wars, asked for suggestions.

Scholars collected 14,000 books and 89,000 written scrolls dating to 2,600 BC and created Qunshu Zhiyao, The Compilation of Books and Writings on Important Governing Principles, 群书治要, whose 500,000 words cover sixty-five governance categories. “The collection has helped me learn from the ancients. When confronted with issues, I am certain of knowing what to do. This is all due to your efforts, my advisors,” said the grateful ruler. His era began a Golden Age and The Compilation became required reading for crown princes.

Since Confucian imperial examination systems were already a thing, Taizong emphasized their importance by executing cheats. To reduce corruption, he required officials’ loyalty to policies, not people, and made Confucian studies mandatory. China flourished for more than a century after his death and the Tang Golden Age conferred on Confucian governance a legitimacy it has never lost.

Getting proper men

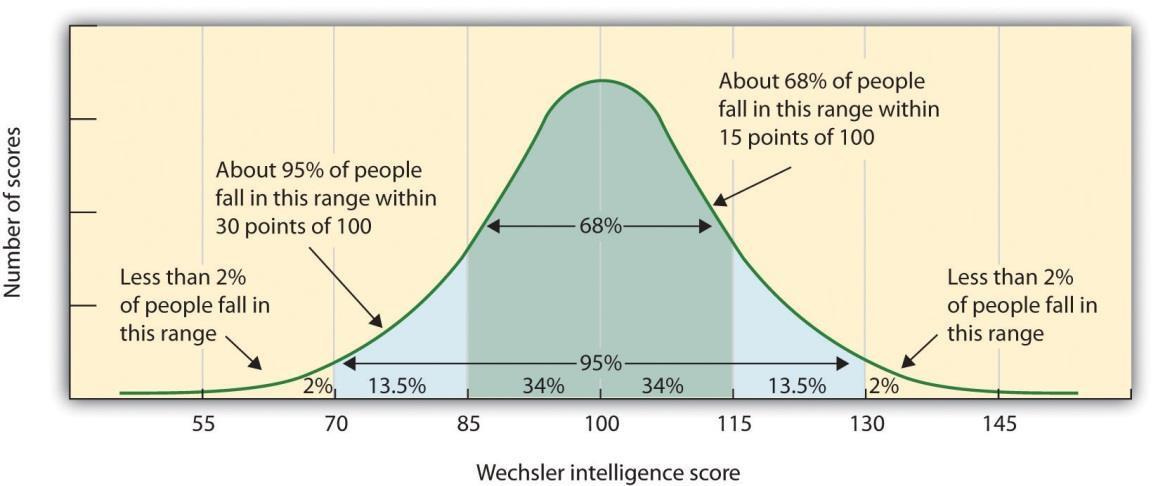

Success in today’s national civil service examination goes to applicants with IQs over 140, the smartest 0.13 percent of humanity, people who would shine in any setting and, as a bonus, are more inclined to honesty than us. President Trump agrees, “People say you don’t like China. No, I love them. But their leaders are much smarter than ours. And we can’t sustain ourselves like that. It’s like playing the New England Patriots and Tom Brady against your high school football team.”

China is again run by honest geniuses who are sworn to sacrifice their lives serving others. Xi’s ‘whole-process people’s democracy’ uses millions of volunteers, endless public surveys and consultations, field trials of all legislation before sending it to Congress, a process that can take decades. They work by consensus – Xi has one of six votes needed to send legislation to Congress, where two-thirds of delegates must approve it – and their long-term approach ensures that future generations will be better off than their parents. Thanks to officials’ subject-matter expertise, dedication to measurable results, and public accountability, they’ve delivered every promise they’ve made for seventy years.

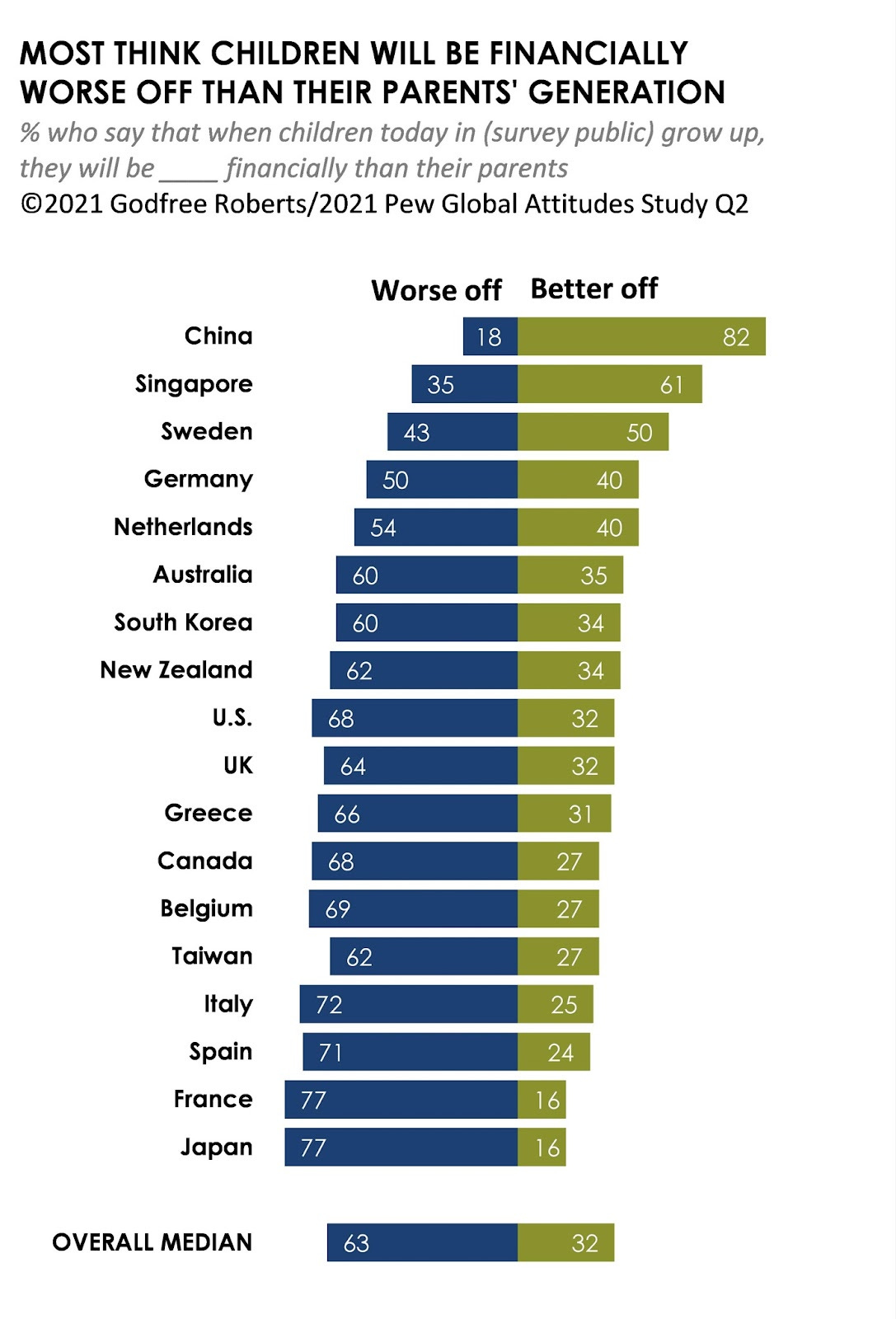

Now, despite desperate attempts to conceal them, the results of China’s past 70 years are becoming visible, and the West is beginning to acknowledge defeat, if only by omission: n 2021, Pew Charitable Trusts surveyed parents' expectations for their children:

The following year, Pew only surveyed ‘most places’:

Golden Age?

China is a vast, ancient, homogeneous, intensely meritocratic, government-centric civilization that has always regarded its head of State as the head of the national family and, adds Wang Yiwei, “The Communist Party of China is a civilization pretending to be a political party”.

No society could copy what the Chinese have created during four millennia of debate, experimentation and socialization – but we can enjoy and be inspired by the spectacle. If China reaches its 2049 goals2, we’ll see the birth of a Golden Age that will outshine the Tang and Song.

And if Washington fails to address its governance problems, the USA will become the Old Europe to China’s newly-developing world.

Zhu Xi, the great 12th century Confucian, defined junzi as second only to Sages like Confucius himself: Junzi can live with poverty; Junzi does more and speaks less. Junzi is loyal, obedient and knowledgeable. Junzi disciplines himself. Among these, ren, compassion, is the core of becoming junzi. To Confucius, the junzi sustained the functions of government and social stratification through his ethical values. Despite its literal meaning, any righteous man willing to improve himself can become a junzi. The junzi rules by acting virtuously himself. It is thought that his pure virtue would lead others to follow his example. The ultimate goal is that government behaves much like family. Thus at all levels filial piety promotes harmony and the junzi acts as a beacon for this piety.

“By 2049 we will reach new heights in every dimension of material, political, cultural and ethical, social, and ecological advancement: we will have modernized of our system and capacity for governance; we will be a global leader in composite national strength and international influence; everyone will be prosperous and enjoy happy, safe and healthy lives and our nation will be a proud, active member of the community of nations.” Xi Jinping.

Here is a wonderfull explanation and illustration of the Chinese Governance in a lecture by Dr. Eric Li

https://youtu.be/Vb835NzfzFw?si=usxX8xy6-qL16Tq6