Atrocity stories are as old as mankind, but two of the most notorious, the Holocaust and Mao’s Great Famine, share these remarkable features:

Nobody saw them happen.

There is no evidence they happened.

Nobody mentioned them for decades after they supposedly happened.

Both attained mythical status.

Both are sustained by massive propaganda campaigns and repressive laws1

Both dehumanize the alleged perpetrator.

Somebody benefited from them.

This first of two parts analyzes the Mao’s Great Famine narrative. We’ll tackle the Holocaust next Wednesday.

Mao’s Great Famine

In Famine killed 7 Million People in the US, Moscow University historian Boris Borisov humorously applied the same techniques to American statistics as Mao’s critics applied to Chinese figures:

Few people have heard about five million American farmers – a million families – whom banks ousted from their land because of debts during the Great Depression. The government did not provide them with land, work, social aid or pensions and every sixth farmer was affected by famine. People were forced to leave their homes and wander without money or belongings in an environment mired in massive unemployment, famine and gangsterism. Market rules were observed strictly: unsold goods could not be given to the poor lest it damage business. They burned crops, dumped them in the ocean, plowed under 10 million hectares of cropland and killed 6.5 million pigs…and The US lost not less than 8,553,000 people from 1931 to 1940.

Afterwards, population growth indices changed twice, instantly. Exactly between 1930-31, the indices drop and stay flat for ten years. No explanation of this phenomenon can be found in the extensive report by the US Department of Commerce’s Statistical Abstract of the United States. The US population was 123 million in 1920. At two percent growth it should have been 271 million in 1960 but, since the 1960 population was only 189 million, the government starved eighty-one million people to death in the intervening forty years.

Looking for trouble

The US was so desperate for a famine in China that Washington tried to create one. After China’s and Canada’s grain harvests failed under a three-year El Nino, Congress embargoed grain shipments to China and assigned the CIA to monitor the embargo’s success. The Agency reported:

4 April 1961: PROSPECTS FOR COMMUNIST CHINA. The Chinese Communist regime is now facing the most serious economic difficulties it has confronted since it concentrated its power over mainland China. As a result of economic mismanagement, and, especially, of two years of unfavorable weather, food production in 1960 was little if any larger than in 1957 at which time there were about 50 million fewer Chinese to feed. Widespread famine does not appear to be at hand, but in some provinces many people are now on a bare subsistence diet and the bitterest suffering lies immediately ahead, in the period before the July harvests. The dislocations caused by the ‘Leap Forward’ and the removal of Soviet technicians have disrupted China’s industrialization program. These difficulties have sharply reduced the rate of economic growth during 1960 and have created a serious balance of payments problem. Public morale, especially in rural areas, is almost certainly at its lowest point since the Communists assumed power, and there have been some instances of open dissidence.

2 May 1962: The future course of events in Communist China will be shaped largely by three highly unpredictable variables: the wisdom and realism of the leadership, the level of agricultural output, and the nature and extent of foreign economic relations. During the past few years all three variables have worked against China. In 1958 the leadership adopted a series of ill-conceived and extremist economic and social programs; in 1959 there occurred the first of three years of bad crop weather; and in 1960 Soviet economic and technical cooperation was largely suspended. The combination of these three factors has brought economic chaos to the country. Malnutrition is widespread, foreign trade is down and industrial production and development have dropped sharply. No quick recovery from the regime’s economic troubles is in sight.

The CIA was not the only one to miss the ‘great famine’. Though he ridiculed the Great Leap Forward as ‘The Great Leap Backward,’ Edgar Snow saw no famine either.

Were the 1960 calamities actually as severe as reported in Peking, the worst series of disasters since the nineteenth century, as Chou En-lai had told me? Weather was not the only cause of the disappointing harvest but it was undoubtedly a major cause. With good weather the crops would have been ample; without it, other adverse factors I have cited – some discontent in the communes, bureaucracy, transportation bottlenecks – weighed heavily. Merely from personal observations in 1960 I know that there was no rain in large areas of northern China for 200-300 days. I have mentioned unprecedented floods in central Manchuria where I was marooned in Shenyang for a week..while Northeast China was struck by eleven typhoons–the largest number in fifty years and I saw the Yellow River reduced to a small stream. Throughout 1959-62 many Western press editorials continued referring to ‘mass starvation’ in China and continued citing no supporting facts. As far as I know, no report by any non-Communist visitor to China provides an authentic instance of starvation during this period. Here I am not speaking of food shortages, or lack of surfeit, to which I have made frequent reference, but of people dying of hunger, which is what ‘famine’ connotes to most of us, and what I saw in the past”.

Historian Dongping Han says the only suicide in the history of his village occurred during the Great Leap.

A woman hanged herself because of family hardship. The Great Leap Forward years were the only time in anybody’s memory that Gao villagers had to pick wild vegetables and grind rice husks into powder to make food. Throughout my twenty years in Gao village, I do not remember any particular time when my family had enough to eat … as a rural resident, life was always a matter of survival. However, the Great Leap Forward made life even more difficult. Our region was hit very hard by natural disasters for two consecutive years… But during the two years of natural disasters, we got relief grain from the Central Government, the provincial Government, Qingdao City, Shanghai City, and many other regions… Whenever and wherever one place had difficulties, people from different places helped. I remember many peasants told me that if it were not for the People’s Government’s help, many people would have starved amid disasters like the one in 1960. By contrast, in Northern Henan Province (where the grain shortage during the Great Leap Forward was supposed to have been severe), five million people starved to death in 1942. The government at that time had done nothing to help the local people.

In the 1990s, on a Guggenheim scholarship, I accompanied Ralph Thaxton, my graduate school advisor, to study the region’s famine. When Ralph told them he had come to study the famine, peasants thought that he was studying the famine of 1942-1943. During that 1942-1943 famine, they said, not only did five million people starve, but many had to sell their land, their houses and children before fleeing their home towns. The local and national governments did nothing to help. But nothing like that took place during the Great Leap Forward. The Great Leap Forward. Dongpin Han.

The Great Famine Narrative

Though dozens of foreign dignitaries, spies, authors and journalists prowled China from 1959-1962, not one saw any sign of famine. Yet in 2010, a German historian claimed that the Great Leap had starved thirty-million people to death, violently killed millions more, destroyed forty percent of China’s homes and littered the country with ‘white elephant’ projects. The Ming Tombs Reservoir (the aquatic venue for the 2008 Olympics), “Was built in the wrong location. It dried up and was abandoned after a few years.”

The book’s cover image, of a starving girl, is the first clue that something is amiss. Nobody had seen such a sight since the Communists came to power and, sure enough, when questioned, the author admitted that the photo was taken by a Life Magazine photographer in 1942. Why did he not use a Great Leap famine image? “Because I couldn’t find one from 1959-62”.

The author’s preface is revelatory “As the modern world struggles to find a balance between freedom and regulation, the catastrophe unleashed at the time [of the Great Leap Forward] stands as a reminder of how profoundly misplaced is the idea of state planning as an antidote to chaos.” He insists that, had Mao maintained the 1953 rate of population growth, China would have had thirty-million more people by 1959 and, therefore, ‘killed’ thirty-million people. He ignored the well-known facts that food shortages cut fertility and that the movement to the cities of millions of young couples moving to cities and joining the labor force negatively impact fertility.

Fitting a linear trend to Mao’s falling death rate, he claimed that mortality should have continued the same decline and, blaming famine for the difference, blamed Mao for the famine.

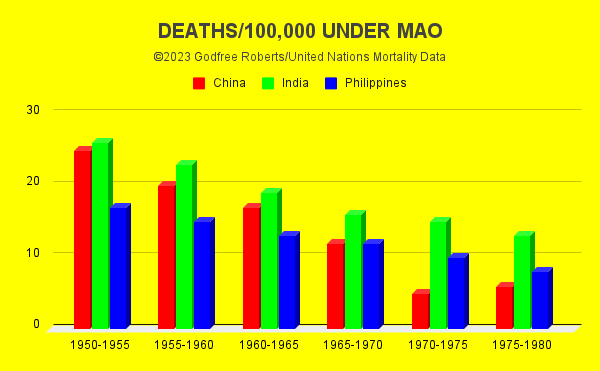

Closer inspection revealed that, by the author’s baseline year of 1958, cooperatives had eradicated disease-bearing pests, established a rudimentary rural health care system and reduced the death rate from twenty to twelve per thousand, a level India reached thirty years later. Nor was there any doubt that the Chinese were better off in 1961 than at any time in the previous century. And if we take as our benchmark Mao’s 1958 achievement of twelve deaths per hundred-thousand, then excess deaths between 1959-1961 would total twelve million.

But the peak death rate, twenty-six per thousand, was identical to India’s in the 1960s, India experienced no general famine, and China’s per capita grain production remained well above India’s throughout the sixties and its distribution system was far more efficient.

Lies, damn lies and statistics

Says Nobelist and famine authority, Amartya Sen, “[India] had, in terms of morbidity, mortality and longevity, suffered an excess in mortality over China of close to four [million] a year during the same [Great Leap Forward] period.”

China’s population increased by eleven million in three years and, though this was below the 1956-1958 rate, its still averaged 5.46 percent, higher than the world average and much higher than the pre-Communist years. During the three famine years thirty-one million people died of all causes which, compared to the 11.4 percent rate of from 1956-1958, represents an extra 8.3 million deaths.

To further test the author’s methodology, historian Boris Borisov applied the same statistical techniques to US Census Bureau figures and found, to his mock horror, that millions of Americans had starved to death during the Great Depression:

Few people know about five million American farmers–a million families–whom banks ousted from their land because of debts during the Great Depression. The US government did not provide them with land, work, social aid, or pensions and every sixth American farmer was affected by famine. People were forced to leave their homes and wander without money or belongings in an environment mired in massive unemployment, famine and gangsterism. At the same time, the US government tried to get rid of foodstuffs which vendors could not sell. Market rules were observed strictly: unsold goods categorized as redundant could not be given to the poor lest it damage business. They burned crops, dumped them in the ocean, plowed under 10 million hectares of cropland and killed 6.5 million pigs. Here is a child’s recollection, “We ate whatever was available. We ate bush leaves instead of cabbage, frogs too. My mother and my older sister died during a year.” The US lost not less than 8,553,000 people from 1931 to 1940. Afterwards, population growth indices change twice, instantly. Exactly between 1930-31 the indices drop and stay on the same level for ten years. No explanation of this phenomenon can be found in the extensive report by the US Department of Commerce Statistical Abstract of the United States.

It was impossible to hide famines even in 1875, news of Ireland’s Potato Famine raced around the globe. When three million Bangladeshis, five percent of the population, starved to death in the 1943 famine the world knew immediately. Yet seven percent of Americans and six percent of Chinese starved to death and nobody noticed?

When an historian asked why the book’s heart-wrenching cover image was taken twenty years before the Great Leap, the author confessed that he could find no photographs of a Great Leap famine, yet the book was hailed as a work of genius, British and American governments paid the author millions and, to this day, most Westerners are convinced that Mao – who spent his life feeding people – starved millions of them to death for no reason.

Real famines

Real famines are impossible to hide. When the British starved one million people starved to death in colonial Ireland in 1846-47, the world knew immediately. Life Magazine covered China’s 1942 famine extensively, as the cover image, above, demonstrates. When Churchill starved three million to death in colonial Bengal in 1943, news and images of the famine raced around the globe. So the notion that eight million Americans starved to death without anyone noticing, or that eleven million Chinese died undetected is just silly.

Even sillier is the notion that six million Jews were slaughtered in a holocaust, as we shall see next Wednesday..

One European writer estimates that there are ‘thousands’ of people in jail there for Holocaust denial and related offenses.