The Reconsidered Series is free. Please pass it along. Part One is here.

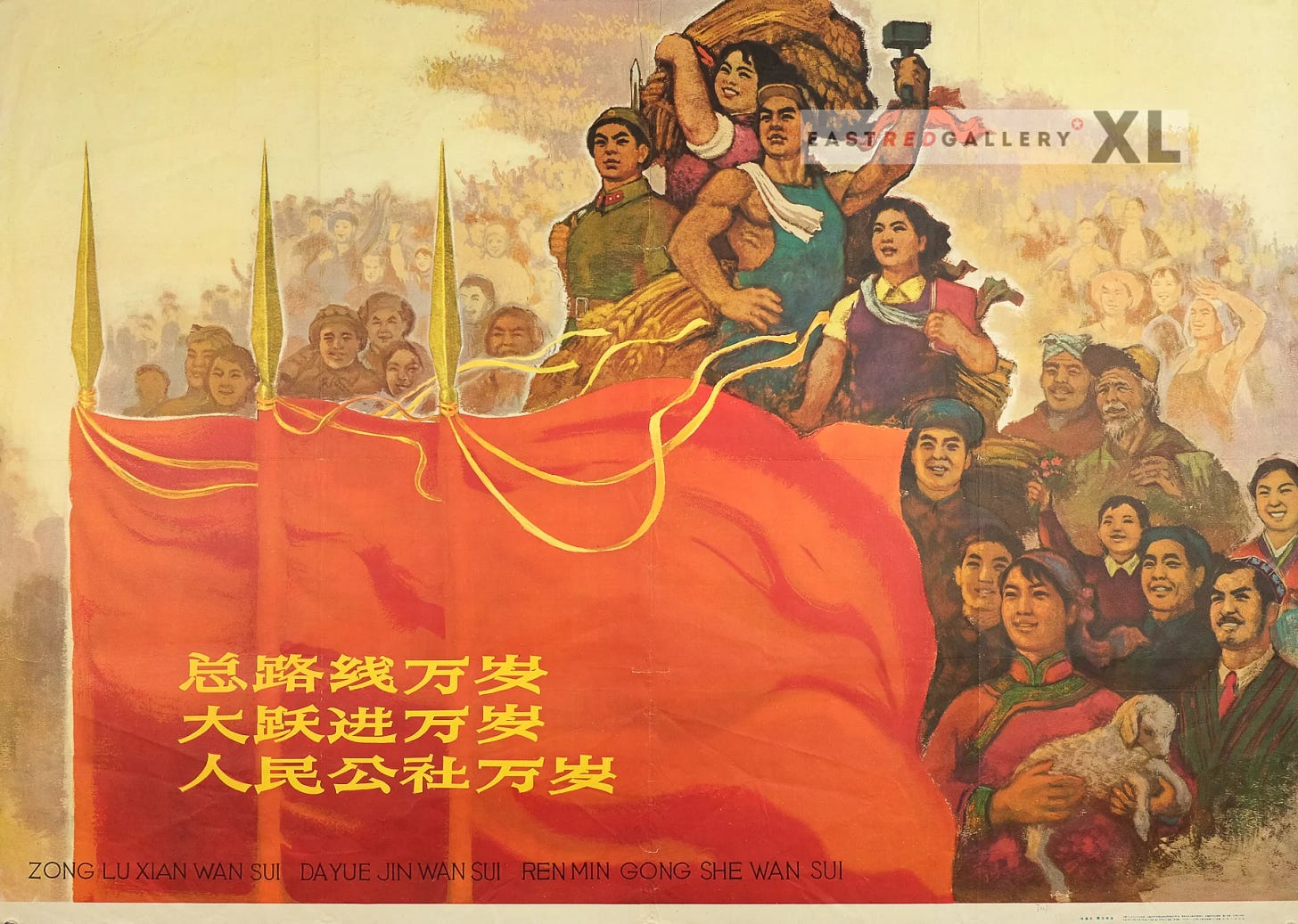

Coal, steel, textile, and electricity generation rose thirty percent, infrastructure rose forty percent in the Great Leap’s three years and peasants built thousands of dams, including nine of today’s ten largest. One, the gigantic Xinfengjiang Reservoir, holds ten cubic meters of clean water for everyone in China, has generated billions of KW, powered rural and urban development, played a vital role in flood control and irrigation, and still waters thirsty Guangdong and Hong Kong.

The higher yields obtained on individual family farms during later years would not have been possible without the vast irrigation and flood-control projects–dams, irrigation works, and river dikes–constructed by collectivized peasants in the 1950s and 1960s. By some key social and demographic indicators, China compared favorably even with middle-income countries whose per capita GDP was five times greater. Economic historian Maurice Meisner.

Indeed, of all the industrial projects China would launch in the next fifteen years, two-thirds were products of the Great Leap.

Temporary setbacks

When villages reported lower harvests at the end of the first year, their superiors blamed temporary setbacks or simple errors. If one region reported improved yields, neighbors felt pressured to make similar claims, especially since communal farming represented the pinnacle of Communist development. Rather than dampen revolutionary zeal, managers convinced themselves that they could make up shortfalls the next season and inflated their figures until reports lost touch with reality. “Some fields would have to be so thick with grain that farmers could walk on them,” scoffed an agronomist. When inspectors reported the results of physical audits, their superiors, entranced by the prospect of Socialism in one generation, rejected their reports and continued diverting grain reserves to traditionally poor regions and newly urbanized industrial workers.

Mao had anticipated bureaucratic resistance, foreign embargoes, official corruption, and peasant reluctance but he never expected China to endure three years of the worst weather in a century. An El Nino cycle (that halved Canada’s prairie wheat crop and created New England’s worst recorded drought) cut China’s cereal harvest by one-third. The spring harvest in the Southwest rice bowl was lost to drought and the Hunan region was flooded. From two hundred million tons in 1958, yields fell to one-hundred forty-three million in 1960. Says Roderick MacFarquhar,

Not surprisingly, given the drought, most of the flooding had been due to the typhoons, more of which had hit the Chinese mainland than in any of the previous 50 years–eleven between June and October. Each storm had lasted longer than usual, averaging ten hours, the longest stretching to 20. Moreover, nature had played an additional trick. The typhoon did not strike north-westwards as usual, but northwards, which added to their impact. There were no high mountains to ward them off, and less rain reached the rest of the country. In the aftermath of the drought and floods came insect pests and plant diseases.

The dejected Party gathered in Lushan where war hero Peng Dehuai bitterly proclaimed Mao’s peasant supporters guilty of ‘petty-bourgeois fanaticism’. Mao protested, “At least thirty percent of them are actively on our side, another thirty percent are pessimists and landlords, while the rest are middle-of-the-roaders. How many people are thirty percent? It’s 150 million who want to run communes and mess halls and do everything cooperatively. They are very enthusiastic and keen. How can you call them petty-bourgeois fanatics?”

Unmoved, his colleagues passed a resolution against “Impetuous actions, utopian dreams, and ignoring the necessary stages of social development which could only be achieved after the lapse of considerable time”.

A crestfallen Mao admitted, “We rushed into a great catastrophe. The communes were organized too quickly. The Great Leap has been a partial failure for which we have paid a high price. The chaos was on a grand scale, and I take responsibility for it… The transition to a dàtóng society1 might take longer than I had envisaged, perhaps as many as twenty Five-Year Plans, but the drive to attain it should never be abandoned”.

Declining to stand for re-election, he wandered “like a mourner at my own funeral”. He bore the rebuke philosophically, “If you can’t handle being impeached by the Party, you are not Party material”.

Next week: The famine–from a peasant’s point of view.

China plans to begin its transition to a dàtóng society in 2049, one hundred years after Mao took power.